Maqam al-Khidr in al-Bassa

مقام الخضرة

מקאם אל-חידר

It is a monumental building, which used to be a jewel of Palestinian village al-Bassa, and now it stands in an Israeli settlement called Shlomi.

W. Khalidi commented on it, “The Muslim shrine is domed and stands deserted in the midst of many trees, including two palms” (1992, 9). A. Petersen described it as follows, “The maqam consists of two parts, a walled courtyard and a domed prayer room. There is a mihrab in the south wall of the courtyard and a doorway in the east wall leading into the main prayer room. The dome is supported by pendentives springing from four thick piers which also support wide side arches. In the middle of the south wall there is a mihrab next to a simple minbar made of four stone steps” (2001, 111).

The maqam is dedicated to a holy man al-Khidr, who is according to the Muslim traditions a Quranic teacher of Musa the Prophet (18:65–82). He is also associated with biblical Elijah the Prophet.

The western wall is 9.20 m long, and the south – 8.85 m. A spacious prayer room let the maqam to be used as a little mosque. The minbar proves that, as well as one more mihrab in the inner yard. Probably, this structure served as a mosque for the Muslims of al-Bassa until a new spacious mosque was built in the settlement in the 19th century. The question is: was there the sheikh's cenotapn inside the maqam? Only the cenotaph could characterize this building as a maqam. Now it is very difficult to find out the existence of the cenotaph. The floor is covered with wreckage, planks and rubbish.

W. Khalidi saw 2 palm trees in the yard, A. Petersen saw only one. Now this very palm tree fell down and blocked the entrance to the shrine. When comparing the photo in Petersen's book with the current view, you may notice further destruction. The south wall of the inner yard is badly damaged, though the mihrab partly survived. The west, east and south walls of the maqam started to collapse. The overall condition of the monument is quite deplorable.

Route. The maqam is located to the east from industrious zone Shlomi and to the north from Highway 899 that goes through the settlement. Here is a historic quartal, where besides the maqam abandoned orthodox and catholic churches, and also a family house of the al-Khuri.

Visited: 19.08.15

In the scientific research literature of the 19th century the maqam of sheikh Abreik is mentioned quite

often. It is one out of five the most famous Muslim shrines in Palestina. A village named Cheik Abrit was marked on Jacotin's map in 1799. During the Palestinian campaign of N. Bonapart the height, where the settlement is located played an important strategic role.

Researchers called the sheikh differently: Abrek, Abreik, Ibreik, Ibrak, Bureik, Burayk. The maqam is dated to the 16th century, though has been often rebuilt since then. C. Conder described sheikh Abreik as a small village situated on a hill with a conspicuous Maqam (Sanctuary) located to the south (SWP I, 273).

At one time J. Sepp thought that the maqam was built in honour of an ancient hero Barak and in memory of the battle that happened there (1863, II 450). Sheikh Abreik himself is described by M. Sharon as a local saint believed to have bestowed the nearby swamp of al-Matba'ah with healing properties that were said to be useful in treating rheutamism and nervous disorders (CIAP III, XXXIX). T. Canaan, who wrote about the shrine of sheikh Abreik in 1927, noted that it was also a site frequented by women seeking to remedy infertility: “After a barren woman has taken a bath in al-Matba'ah she washes herself in Ein Ishaq ["Spring of Isaac"]; she goes then to ash-shekh Ibreik to offer a present” (1927, 111).

A double-domed structure is well observed from Road 722. It is located on the high hill, near a horseman monument of Alexander Zaid, which was established in 1941. The maqam consists of 3 rooms: in the eastern and central parts there are domed chambers (5.0 x 5.0 m), in the southern wall of each there is a mihrab. In the very western chamber a cenotaph stands in front of the mihrab. On the east a space without a roof borders with the domed chambers, which can be called a hall. All the walls inside the maqam are decorated with arched curves. The structure is 3.20 m high.

You can get inside the maqam by 2 ways. First, you can enter the hall through a door in south wall, and then through a small arched doorway get to the central domed chamber (now empty), and then via a small rectangular entrance you to the western domed chamber with a cenotaph. Another entrance to the maqam is through a wide doorway of the north wall in the central domed chamber.

Along the north wall of the hall there are stone stairs leading to the roof. When on the roof you may see that both domes of the maqam have a modern cladding. It is obvious that this important cultural object is under protection. All the entrances and windows are covered with iron bars, and from time to time the maqam is circled with a metal bar fence.

We should add that on the ground near the northwestern corner of the building there is a split off column cap of an ancient column.

Route. You can reach the maqam from Road 722 by following an asphalt road which leads to Alexander Zaid's monument. This road is commonly known to everybody who visit Beit She'arim National Park.

Visited: 20.08.15

Ahmad Abu ‘Atabi was a distinguished soldier in the troops of Saladin and became famous during the Crusaders' Siege of Acre (1189–1191). After his death he was buried with honours nearby this city. A huge tomb of Abu ‘Atabi is equal in size to Rachel's Tomb in Bethelem and Joseph's Tomb in Nablus.

Till recent times there were two Arabic inscriptions on the maqam's wall, one reads that the tomb was built in 1727–28 CE. Anyway, the scientists think this Muslim shrine dates back to the Mamluk period. Probably, in the early 18th century it was restored or significantly rebuilt, and that was reflected in the Arabic inscription.

In 1738 R. Pococke described the maqam with admiration, “On the highest ground of it are the ruins of a very strong square tower, and near it, is a mosque, a tower, and other great buildings; the place is called Abouotidy, from a Sheik who was buried there” (1745, II 54). In 1760, abbe Mariti called the place Bоhattebe: “The southern gate of Acre open towards a highway, and conducts to Bоhattebe, situated on a small eminence, which contains the ruins of an ancient temple, employed as a place of worship both by the Turks and Christians, but at different periods. Some paces further is a mosque, remarkable on account of its burying-ground, in which was interred a prodigious number of infidels, who perished under the walls of Acre” (1792, 332).

In March 1799 during the siege of Acre Bonaparte troops set their camp nearby Abu ‘Atabi tomb. “On 19th of March the avant-garde occupied the Mosque mountain (fr. Le mont de la Mosque), which dominated over the whole plain of Saint-Jean-d'Acre, and also over the city” – Le Livre Campagne d'Égypte et de Syrie: mémoires pour servir à l'histoire Napoleon – says the book with memoires of Napoleon and published by general Bertrand (1847, II 58). The maqam of Abu ‘Atabi should be perceived as this “mosque”. Nearby or even inside there was a hospital where the wounded soldiers were treated (1847, II 60). Sometimes Napoleon himself visited the injured. At the same place, near the “mosque” the famous general met with local thieves who joined him and standing on the maqam step delivered a speech for them. However, all Napoleon actions were in vain: Acre had not been captured, and he had to retreat back first to Egypt, then to France.

During the Siege of Acre only Napoleon was recollecting this “mosque”. Obviously, it well stuck to his mind. His generals and companions did not mention it in their memoires. When being in exile on Saint Helena Island, not a long time before his death, the emperor himself jotted down a plan-scheme of the siege of Acre in 1799 and again he marked that very mosque with letter “M”, which actually was the tomb of Abu ‘Atabi.

It is clear that Napoleon took all Muslim worship objects as mosques and not only Muslim, - he even called Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow a mosque. However, two centuries later a Palestinian historian W. Khalidi called a Muslim shrine nearby Acre the same way, ”The mosque, a stone structure with a dome and vaulted ceilings, has been turned into a private home for a Jewish family” (1992, 23). In 1994 A. Petersen also noticed that maqam Abu ‘Atabi was used as a loging. In fact, a family (Arabic, not Jewish) still lives in the shrine.

The owners of the house are very friendly and with readiness show the guest of the shrine to the burial chamber, which is more like a storage room. A dim lighting doesn't allow to watch the details of the chamber. Among many huge bags and packs there is cenotaph Abu ‘Atabi, carefully covered with a green cloth.

As A. Petersen says, “This structure stands on the west slope of a low hill and is built on a raised platform or terrace. The two main elements of the building are the large domed chamber and the prayer room to the north. The corners of the building are strengthened by large external buttresses. Since 1948 a number of extra rooms have been added to the shrine which now forms the centre of a small residential complex. The prayer room now functions as a living room, although the shrine itself is still in use and is kept clear of domestic clutter.

Entered through a doorway in the north wall, the prayer hall acts as an ante-room for the shrine. The prayer room is entered through a doorway in the north-east corner and is roofed with a folded cross-vault with a small dome at the apex. The sides of the vault are decorated with small moulded triangles whilst the dome in the centre is decorated with a swirled disc motif. A pair of double windows are set into the west wall and there is a mihrab flanked by two windows in the centre of the south wall. The north wall of the room appears to be modern, suggesting that the room was originally open on this side. In the middle of the east wall is the doorway through to the domed chamber containing the tomb of Abu ‘Atabi. Above the doorway are two inscriptions set one above the other. Written on an upright rectangular marble panel, the upper inscription consists of eight lines of naskhi divided into four cartouches. At the end of this inscription the date of 1140 H. (1727–1728 CE.) is given. The fragmentary lower inscription is written on a roughly rectangular piece of marble in a larger ornamental script which may be earlier, possibly dating to the Mamluk period.

This structure stands on the west slope of a low hill and is built on a raised platform or terrace. The two main elements of the building are the large domed chamber and the prayer room to the north. The corners of the building are strengthened by large external buttresses. Since 1948 a number of extra rooms have been added to the shrine which now forms the centre of a small residential complex. The prayer room now functions as a living room, although the shrine itself is still in use and is kept clear of domestic clutter.

The interior of the tomb chamber is a square area covered with a tall dome resting on triangular pendentives supported by wide arches which spring from the ground. The tomb or cenotaph of Abu ‘Atabi is in the centre of the room. The mihrab is a plain undecorated niche in the middle of the south wall. The tomb chamber is lit by two small windows in the south wall above the mihrab and another high up in the west wall” (2001, 65).

Two Arabic inscriptions are still above the entrance to the burial chamber. There is a carton plate near the tombstone which tells about Abu ‘Atabi. Obviously, there are also basement rooms under the flat of the Arabic family, which one cannot enter. One thing should be (spelling) mentioned as well: the white maqam's dome was painted light-blue in 2010, not green as nowadays Muslim usually use.

Pay attention to the décor of a little window in the south wall: this architecture element can be dated to the Mamluk period.

Across the street, opposite to Maqam Abu ‘Atabi there is a cemetery where the tomb of Muhammad ‘Ali, the son of Bahaullah, is dominating over others. When we were there the cemetery was locked.

Route. Maqam Abu ‘Atabi relates to a former Palestinian village al-Manshiya, which was 2 km to the northeast from Acre. Now the maqam is located within Acre city, to the north from old Muslim cemetery.

Visited: 19.08.15

W. Khalidi commented on it, “The Muslim shrine is domed and stands deserted in the midst of many trees, including two palms” (1992, 9). A. Petersen described it as follows, “The maqam consists of two parts, a walled courtyard and a domed prayer room. There is a mihrab in the south wall of the courtyard and a doorway in the east wall leading into the main prayer room. The dome is supported by pendentives springing from four thick piers which also support wide side arches. In the middle of the south wall there is a mihrab next to a simple minbar made of four stone steps” (2001, 111).

View from the west

Photo of 1992 (from the book by A. Petersen)

The maqam is dedicated to a holy man al-Khidr, who is according to the Muslim traditions a Quranic teacher of Musa the Prophet (18:65–82). He is also associated with biblical Elijah the Prophet.

The western wall is 9.20 m long, and the south – 8.85 m. A spacious prayer room let the maqam to be used as a little mosque. The minbar proves that, as well as one more mihrab in the inner yard. Probably, this structure served as a mosque for the Muslims of al-Bassa until a new spacious mosque was built in the settlement in the 19th century. The question is: was there the sheikh's cenotapn inside the maqam? Only the cenotaph could characterize this building as a maqam. Now it is very difficult to find out the existence of the cenotaph. The floor is covered with wreckage, planks and rubbish.

View from the south

View from the east

View from the north

The minbar and mihrab in the south wall

Inside the maqam

The dome

W. Khalidi saw 2 palm trees in the yard, A. Petersen saw only one. Now this very palm tree fell down and blocked the entrance to the shrine. When comparing the photo in Petersen's book with the current view, you may notice further destruction. The south wall of the inner yard is badly damaged, though the mihrab partly survived. The west, east and south walls of the maqam started to collapse. The overall condition of the monument is quite deplorable.

Route. The maqam is located to the east from industrious zone Shlomi and to the north from Highway 899 that goes through the settlement. Here is a historic quartal, where besides the maqam abandoned orthodox and catholic churches, and also a family house of the al-Khuri.

Visited: 19.08.15

Coordinates: 33°04'41.4"N 35°08'36.2"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Khalidi 1992, 9; Petersen 2001, 111; Zochrot: al-Bassa

Maqam sheikh Abreik (Bureik)

مقام الشيخ بريك

קבר שייח' אבריק

Researchers called the sheikh differently: Abrek, Abreik, Ibreik, Ibrak, Bureik, Burayk. The maqam is dated to the 16th century, though has been often rebuilt since then. C. Conder described sheikh Abreik as a small village situated on a hill with a conspicuous Maqam (Sanctuary) located to the south (SWP I, 273).

View from the north

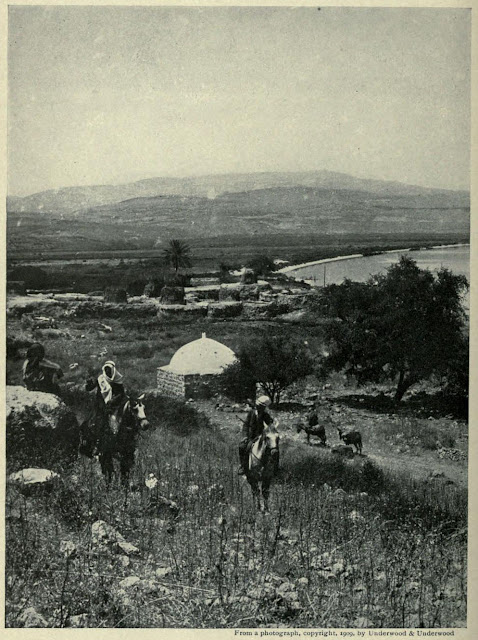

Photo of 1932

At one time J. Sepp thought that the maqam was built in honour of an ancient hero Barak and in memory of the battle that happened there (1863, II 450). Sheikh Abreik himself is described by M. Sharon as a local saint believed to have bestowed the nearby swamp of al-Matba'ah with healing properties that were said to be useful in treating rheutamism and nervous disorders (CIAP III, XXXIX). T. Canaan, who wrote about the shrine of sheikh Abreik in 1927, noted that it was also a site frequented by women seeking to remedy infertility: “After a barren woman has taken a bath in al-Matba'ah she washes herself in Ein Ishaq ["Spring of Isaac"]; she goes then to ash-shekh Ibreik to offer a present” (1927, 111).

A double-domed structure is well observed from Road 722. It is located on the high hill, near a horseman monument of Alexander Zaid, which was established in 1941. The maqam consists of 3 rooms: in the eastern and central parts there are domed chambers (5.0 x 5.0 m), in the southern wall of each there is a mihrab. In the very western chamber a cenotaph stands in front of the mihrab. On the east a space without a roof borders with the domed chambers, which can be called a hall. All the walls inside the maqam are decorated with arched curves. The structure is 3.20 m high.

View from the north-west

A small arched doorway to the central domed chamber

The central domed chamber

The western domed chamber with a cenotaph

You can get inside the maqam by 2 ways. First, you can enter the hall through a door in south wall, and then through a small arched doorway get to the central domed chamber (now empty), and then via a small rectangular entrance you to the western domed chamber with a cenotaph. Another entrance to the maqam is through a wide doorway of the north wall in the central domed chamber.

Along the north wall of the hall there are stone stairs leading to the roof. When on the roof you may see that both domes of the maqam have a modern cladding. It is obvious that this important cultural object is under protection. All the entrances and windows are covered with iron bars, and from time to time the maqam is circled with a metal bar fence.

We should add that on the ground near the northwestern corner of the building there is a split off column cap of an ancient column.

Route. You can reach the maqam from Road 722 by following an asphalt road which leads to Alexander Zaid's monument. This road is commonly known to everybody who visit Beit She'arim National Park.

Visited: 20.08.15

Coordinates: 32°42'03.1"N 35°07'44.0"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Sepp 1863, II 450; Quarterly statement V 47; Conder 1879, I 163; Conder, 1887, 254; SWP 1881, 131; SWP I, 273; Palmer 1881, 116 (Sheet V); Stewardson 1888, 139; Meistermann 1907, 363; Mülinen, DPV 1908, 194; Canaan 1927, 68, 111; Ariel 1996, 105; Sharon, CIAP III, XXXVII–XLV;

Addition: Panorama

Maqam sheikh Abu ‘Atabi (‘Utba)

مقام الشيخ أبو عتبة

קבר שייח' אבו עתבה

Till recent times there were two Arabic inscriptions on the maqam's wall, one reads that the tomb was built in 1727–28 CE. Anyway, the scientists think this Muslim shrine dates back to the Mamluk period. Probably, in the early 18th century it was restored or significantly rebuilt, and that was reflected in the Arabic inscription.

In 1738 R. Pococke described the maqam with admiration, “On the highest ground of it are the ruins of a very strong square tower, and near it, is a mosque, a tower, and other great buildings; the place is called Abouotidy, from a Sheik who was buried there” (1745, II 54). In 1760, abbe Mariti called the place Bоhattebe: “The southern gate of Acre open towards a highway, and conducts to Bоhattebe, situated on a small eminence, which contains the ruins of an ancient temple, employed as a place of worship both by the Turks and Christians, but at different periods. Some paces further is a mosque, remarkable on account of its burying-ground, in which was interred a prodigious number of infidels, who perished under the walls of Acre” (1792, 332).

View from the south-east

Photo of 1994 (from the book by A. Petersen)

In March 1799 during the siege of Acre Bonaparte troops set their camp nearby Abu ‘Atabi tomb. “On 19th of March the avant-garde occupied the Mosque mountain (fr. Le mont de la Mosque), which dominated over the whole plain of Saint-Jean-d'Acre, and also over the city” – Le Livre Campagne d'Égypte et de Syrie: mémoires pour servir à l'histoire Napoleon – says the book with memoires of Napoleon and published by general Bertrand (1847, II 58). The maqam of Abu ‘Atabi should be perceived as this “mosque”. Nearby or even inside there was a hospital where the wounded soldiers were treated (1847, II 60). Sometimes Napoleon himself visited the injured. At the same place, near the “mosque” the famous general met with local thieves who joined him and standing on the maqam step delivered a speech for them. However, all Napoleon actions were in vain: Acre had not been captured, and he had to retreat back first to Egypt, then to France.

During the Siege of Acre only Napoleon was recollecting this “mosque”. Obviously, it well stuck to his mind. His generals and companions did not mention it in their memoires. When being in exile on Saint Helena Island, not a long time before his death, the emperor himself jotted down a plan-scheme of the siege of Acre in 1799 and again he marked that very mosque with letter “M”, which actually was the tomb of Abu ‘Atabi.

It is clear that Napoleon took all Muslim worship objects as mosques and not only Muslim, - he even called Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow a mosque. However, two centuries later a Palestinian historian W. Khalidi called a Muslim shrine nearby Acre the same way, ”The mosque, a stone structure with a dome and vaulted ceilings, has been turned into a private home for a Jewish family” (1992, 23). In 1994 A. Petersen also noticed that maqam Abu ‘Atabi was used as a loging. In fact, a family (Arabic, not Jewish) still lives in the shrine.

The owners of the house are very friendly and with readiness show the guest of the shrine to the burial chamber, which is more like a storage room. A dim lighting doesn't allow to watch the details of the chamber. Among many huge bags and packs there is cenotaph Abu ‘Atabi, carefully covered with a green cloth.

As A. Petersen says, “This structure stands on the west slope of a low hill and is built on a raised platform or terrace. The two main elements of the building are the large domed chamber and the prayer room to the north. The corners of the building are strengthened by large external buttresses. Since 1948 a number of extra rooms have been added to the shrine which now forms the centre of a small residential complex. The prayer room now functions as a living room, although the shrine itself is still in use and is kept clear of domestic clutter.

Entered through a doorway in the north wall, the prayer hall acts as an ante-room for the shrine. The prayer room is entered through a doorway in the north-east corner and is roofed with a folded cross-vault with a small dome at the apex. The sides of the vault are decorated with small moulded triangles whilst the dome in the centre is decorated with a swirled disc motif. A pair of double windows are set into the west wall and there is a mihrab flanked by two windows in the centre of the south wall. The north wall of the room appears to be modern, suggesting that the room was originally open on this side. In the middle of the east wall is the doorway through to the domed chamber containing the tomb of Abu ‘Atabi. Above the doorway are two inscriptions set one above the other. Written on an upright rectangular marble panel, the upper inscription consists of eight lines of naskhi divided into four cartouches. At the end of this inscription the date of 1140 H. (1727–1728 CE.) is given. The fragmentary lower inscription is written on a roughly rectangular piece of marble in a larger ornamental script which may be earlier, possibly dating to the Mamluk period.

This structure stands on the west slope of a low hill and is built on a raised platform or terrace. The two main elements of the building are the large domed chamber and the prayer room to the north. The corners of the building are strengthened by large external buttresses. Since 1948 a number of extra rooms have been added to the shrine which now forms the centre of a small residential complex. The prayer room now functions as a living room, although the shrine itself is still in use and is kept clear of domestic clutter.

The interior of the tomb chamber is a square area covered with a tall dome resting on triangular pendentives supported by wide arches which spring from the ground. The tomb or cenotaph of Abu ‘Atabi is in the centre of the room. The mihrab is a plain undecorated niche in the middle of the south wall. The tomb chamber is lit by two small windows in the south wall above the mihrab and another high up in the west wall” (2001, 65).

View from the south

View from the east

The tombstone

Two Arabic inscriptions are still above the entrance to the burial chamber. There is a carton plate near the tombstone which tells about Abu ‘Atabi. Obviously, there are also basement rooms under the flat of the Arabic family, which one cannot enter. One thing should be (spelling) mentioned as well: the white maqam's dome was painted light-blue in 2010, not green as nowadays Muslim usually use.

Pay attention to the décor of a little window in the south wall: this architecture element can be dated to the Mamluk period.

Across the street, opposite to Maqam Abu ‘Atabi there is a cemetery where the tomb of Muhammad ‘Ali, the son of Bahaullah, is dominating over others. When we were there the cemetery was locked.

Route. Maqam Abu ‘Atabi relates to a former Palestinian village al-Manshiya, which was 2 km to the northeast from Acre. Now the maqam is located within Acre city, to the north from old Muslim cemetery.

Visited: 19.08.15

Coordinates: 32°56'14.7"N 35°05'30.4"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Pococke 1745, II 54; Mariti 1792, 332; Bertrand 1847, II 58; Palmer 1881, 39 (Sheet III); Khalidi 1992, 23–24; Sharon, CIAP I, 34–36; Petersen 2001, 65; The Archaeological Survey of Israel

Addition: Panorama

Maqam sheikh Abu Shusha

مقام الشيخ ابو شوشة

קבר שייח' אבּוּ שוּשָה

In a former Palestinian village Ghuweir Abu Shusha (2 km from Lake Kinneret) there were three Muslim shrines. Only one has survived: the tomb of the sheikh, located on the top of the hill.

This shrine is of a respectable age, as E. Robinson witnessed it already in 1838. He commented it briefly, “A wely with a white dome marks the spot” (1841, III 285). J. Sepp did the same, “A white dome dominated the wely of a Muslim holy man called Shusha, which means das Ros” (1863, II 171).

In 1863 V. Guérin watched this maqam, “At 5:55 I climbed up the hill, topped with a small wely dedicated to Abu Shusha. He gave his name to the ruins around it, that's why they are called Khirbet Abu Shusha. There are remains of the mentioned holy man inside the shrine. Nearby there are a few Muslim shrines and a dozen huts built from volcanic stone” (Galilee I 209–210).

P. B. Meistermann was the next who described the shrine, “Then, 4 km from the lake we climb up the hill, topped with a wely of a small Arabic settlement called Abu Shusha” (1907, 418). We should mentioned that Meistermann exaggerated the distance from the lake to the settlement. But now you can observe Lake Kinneret from the maqam's dome, as the hill is covered with oleaginous plants.

In fact, the shrine is a real religious complex. Spacious rooms (now destroyed) border the maqam from the north and west. The maqam is built from black basalt (7.35 x 6.80 m). In the western room there saved 2 half-round arches. The entrance was from the north. Each wall was decorated with arched curves. There are small windows in the western and eastern walls. There is no mihrab in the south wall. A cenotaph is covered with a green cloth, on the surface of which there laid Muslim holy books. Though inscriptions on the walls are all Jewish.

The maqam is in quite good condition; however, the destruction has already begun. A part of the south wall has partly collapsed. On some stones there left traces of plaster with which the maqam used to be covered.

View from the south-east

View from the west

Arched vaults in the room west of the tomb

Inside the maqam

Inside the maqam

Route. To reach the maqam you should turn to a track road on the 424th km of Highway 90 (opposite the entrance to kibbutz Ginnosar). Over 500 m on this track road you should stop and climb up a steep slope on foot. The shrine is on the top of the hill.

We should mention that W. Khalidi describes this object as follows, “The shrine of Shaikh Muhammad and the remains of a mill can be seen among piles of stones and a few olive trees” (1992, 517). Obviously, the Palestinian historian confused this maqam with two others which were also located in Ghuweir Abu Shusha and which now have completely dissapeared. These maqams belonged to another sheikhs, both called Muhammed. One of those shrines was to the west from the maqam of sheikh Abu Shusha, near spring al-Bassa, another one – to the south-east, near a mill. At the suggestion of W. Khalidi the name of the survived maqam also moved to Wikipedia.

Actually the remains of three mills survived (besides the maqam of sheikh Abu Shusha) on the territory of the former Palestinian village. Please find below an aerophoto with all objects marked. They are located in accordance with the 1942 British map.

Visited: 21.08.15

Coordinates: 32°51'13.7"N 35°30'26.8"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Robinson 1841, III 285; Sepp 1863, II 171; Guérin, Galilee I 209–210; Conder 1877, 96; De Vaux 1883, 362; Meistermann 1907, 418; Khalidi 1992, 517

Maqam sheikh Hussein

مقام الشيخ حسين

קבר שייח' חוסין

All visitors of Hurvat Ga'aton (Hebrew: Khirbet Jathun – quite a popular place) go to see an abandoned farmhouse of the 19th century. On the stand set by KKL you can read, “The eastern part of the structure is the highest and contains the majority of ancient ruins. They are the remains of buildings, oil press factories and a Muslim cemetery, with the tomb of sheikh Hussein in the centre of it.”

Now it is difficult to see the Muslim shrine in the bushes , it's much older than the farmhouse.

A. Petersen visited the maqam in 1991, when it used to be in much better condition. The Petersen's description wholly coincides with what we see now.

“This structure is located amidst trees at the east end of the site. A number of graves in the vicinity suggest that the area developed as a cemetery.

The maqam consists of two parts, a domed chamber and an outer room. The outer room is approximately square (6.66 x 6.54 m) with a niche in the east wall and a tree in the middle. This room was probably entered through a doorway on the north side, however because the north wall is now in ruins, the exact position of the original entrance is uncertain. It is not clear whether this room was ever roofed although traces of piers in the south-west, south-east, and north-east corners suggest that it may have been covered with a cross-vault. The outer room was certainly built later than the inner room as can be seen from the butt joint in the south-west corner.

The inner chamber is entered through a low doorway in the south wall of the outer room. Half of the dome has survived although the eastern part has collapsed. The dome was supported by spherical pendentives resting on shallow arches springing from corner piers. In the south wall the top part of a mihrab can be seen although the lower part is below the current floor level. On the outside a set of stairs runs up the north wall to the roof.

The date of construction is not known although the use of spherical pendentives rather than squinches suggest an Ottoman date” (2001, 180–181).

Now the maqam has collapsed by more than three fourths: only the south wall with a mihrab and a part of the west wall with a pistachio tree on it (Pistacia palaestina) are left. The outer room is actually a heap of stones, though the holy tree is still there. No trace is left from the Muslim tombs that A. Petersen saw nearby the maqam. The Archaeological Survey of Israel tells about ancient walls near the maqam. We did not find them either.

Route. Now the maqam is surrounded with thorny impassable bushes, thus it's almost impossible to reach it. There is no path or sign. We do not recommend to attempt to reach it. However, if there is a brave man, we attach a detailed plan of Khirbet Jathun (Hurvat Ga'aton). It's important to keep in mind that in thick bushes between the farmhouse and maqam there are a few barbed wire fences. Each of them is not easy to pass.

Visited: 19.08.15

Coordinates: 33°00'44.0"N 35°11'43.2"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Palmer 1881, 54 (Sheet III); Stewardson 1888, 139; Petersen 2001, 180–181; The Archaeological Survey of Israel

Maqam sheikh Kuweiyis

مقام الشيخ ﺍﻟﻛﻭﻳﺱ

קבר שייח' כוויס

This shrine is located in a picturesque place, on a steep slope in gorge Nahal ‘Amud. Sheikh Kuweiyis (“the Pretty”) is buried there. It is that rare case when a Muslim kept his non-Arabic (Persian) name, which came down in the history.

The maqam's size is 7.10 x 6.40 m. The entrance is in the east wall, where there is a smooth site. The west wall stands on the edge of precipitous cliffs falling down into a deep gorge. There is a partly damaged window in the west wall which overlooking Nahal ‘Amud. The walls of the domed room are decorated with arched curves, a 1.40 m high mihrab is in the niche. The dome of the shrine partly collapsed. The cenotaph has disappeared, but there are its traces on the floor.

View from the east

View from the north

View from the north-east

View from the west

The mihrab

Inside the maqam

The overall condition of the monument is satisfying. The workers of reservation Nahal ‘Amud keep it under control and do not let it collapse. Recently in the east wall of the maqam there appeared a dangerous hole to the left from the entrance, which was later filled up.

Route: We pass Safed (nearby Highway 89) by the asphalt road through Limonim forest and over 1.5 km stop near spring ‘Ein Howas. The maqam stands in 350 m to the west from the spring. A touristic path pass by the maqam along Nahal ‘Amud.

Visited: 20.08.15

Coordinates: 32°57'05.7"N 35°28'42.7"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Palmer 1881, 93 (Sheet IV); Stewardson 1888, 139

Maqam sheikh Marzuk

مقام الشيخ مرزوق

קבר שייח' מרזוק

Only the maqam of sheikh Marzuk out of 24 Muslim shrines on the Golan Heights remained intact till the present time. It belonged to the former Turkoman village al-‘Ulleika. “Opposite the village, on the other side of the valley, on the Via maris, lies the beautifully built cupola kind of Wely of the Sheikh Marzuk. The whitewashed building serves as a land-mark for a long distance. The tomb is supposed to contain the remains of the Saint and some of his relatives; close by is a graveyard” — said G. Schumacher (1888, 259).

The remains of the white paint are still visible on the walls and on the dome of the structure made of black basalt stones.

The maqam is 9.50 x 6.10 m and consists of two rooms: a Hall room with arched ceiling (the western room) and a domed Burial chamber (the eastern room). One can get into the hall through a door in the north wall, and turning to the left through a low doorway get into the Burial chamber. In the latter there in a mihrab in the south wall, with the remains of a cenotaph above it. In the basement of the dome on the south side there is a small window. In the Hall room pilgrims might have a night rest. Obviously, there was a special niche in the west wall for them.

A fragment of an ancient lintel decorated with a relief of a cross circumscribed within a circle and the letters alpha and omega is integrated in the lintel above the entrance. The lintel is broken lengthwise and only half of the cross remains. It was placed with the decorated side facing down. Several ashlar stones are also integrated in the walls of the structure.

There are remains of the Muslim cemetery around the maqam. Some of the tombs are built of ashlar stones among them lintels and doorjambs also. Many of the stones standing at the ends of the village seem to be Byzantine gravestones, but there are no inscriptions on them.

An old caravan road which G. Schumacher called a Rome Via maris that lead from the Bridge Banat Yakub to Quneitra and passed between the maqam and the Wadi al-‘Ulleika (Gilabun Stream). Now it is almost invisible. On the north river bank there are barely visible ruins of the village al-‘Ulleika. There are also the remains of two ancient windmills.

Route. You can reach the maqam from Highway 91. At the 19th km of this Highway before an Israeli military base you should turn to the north, to the asphalt road follow it for 390 m, till the Nahal Gilbon (Gilabun Stream). The structure is 200 m to the west.

Visited: 19.10.19

The remains of the white paint are still visible on the walls and on the dome of the structure made of black basalt stones.

View from the north

View from the south

View from the west

The maqam is 9.50 x 6.10 m and consists of two rooms: a Hall room with arched ceiling (the western room) and a domed Burial chamber (the eastern room). One can get into the hall through a door in the north wall, and turning to the left through a low doorway get into the Burial chamber. In the latter there in a mihrab in the south wall, with the remains of a cenotaph above it. In the basement of the dome on the south side there is a small window. In the Hall room pilgrims might have a night rest. Obviously, there was a special niche in the west wall for them.

A fragment of an ancient lintel decorated with a relief of a cross circumscribed within a circle and the letters alpha and omega is integrated in the lintel above the entrance. The lintel is broken lengthwise and only half of the cross remains. It was placed with the decorated side facing down. Several ashlar stones are also integrated in the walls of the structure.

Hall room

Entrance to Burial chamber

Burial chamber

The mihrab

There are remains of the Muslim cemetery around the maqam. Some of the tombs are built of ashlar stones among them lintels and doorjambs also. Many of the stones standing at the ends of the village seem to be Byzantine gravestones, but there are no inscriptions on them.

An old caravan road which G. Schumacher called a Rome Via maris that lead from the Bridge Banat Yakub to Quneitra and passed between the maqam and the Wadi al-‘Ulleika (Gilabun Stream). Now it is almost invisible. On the north river bank there are barely visible ruins of the village al-‘Ulleika. There are also the remains of two ancient windmills.

Fragment of the map of G. Schumacher

Route. You can reach the maqam from Highway 91. At the 19th km of this Highway before an Israeli military base you should turn to the north, to the asphalt road follow it for 390 m, till the Nahal Gilbon (Gilabun Stream). The structure is 200 m to the west.

Visited: 19.10.19

Coordinates: 33°03'01.2"N 35°42'02.1"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

Maqam sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan (Majdal)

مقام الشيخ محمد ﺍﻠﺮﺴﻠﻦ

קבר שייח' מוחמד אל-רסלן

The Palestinian village of Majdal (near Tiberias) had two shrines: the maqam of sheikh Muhammad al-‘Ajami to the north of the village and the maqam of sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan (or ar-Ruslan) to the south of the village. The first shrine was mentioned by V. Guérin in 1863. He arrived in Majdal from the north, moving from Khan al-Minya. “At seven and twenty minutes I crossed the fifth important stream, called Wadi al-Hammam. Behind him is a wely dedicated to the saint Sidi al-Adjemy. At seven o'clock twenty-five minutes I reach el-Majdel, a village which I pass without stopping, having already visited it enough” (Galilee I 249).

A Russian traveler A. Olesnitsky, who visited the settlement in 1874, wrote in his report, “Nowadays Mejdel is a poor village. Two remains of towers built by Arabs and a white plastered tomb of the village sheikh are the only places of interest“ (II, 452).

A English traveler Lady Burton in her private journals published in 1875, she writes, “First we came to Magdala (Mejdel)... There is a tomb here of a Shaykh (El Ajami), the name implies a Persian Santon; there is a tomb seen on a mountain, said to be that of Dinah, Jacob's daughter” (1875, 245). Perhaps, the tomb of Dina, Jacob's daughter, should be understood as the second Muslim shrine — the maqam of sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan.

A photo of maqam sheikh Muhammad al-‘Ajami is found in C. McCovn's article “Muslim Shrines in Palestine” (1922, 78). Next to the maqam is a sacred tree. However, the image is rather unclear.

Location of Majdal's shrines on the PEF map of 1880

Location of Majdal's shrines on the British map

After 1948 settlement Majdal became depopulated and was leveled with the ground with Israeli bulldozers (Schaberg 2004, 49). Then the maqam of sheikh Muhammad al-‘Ajami disappeared. But the maqam of sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan, located south of the village, has survived. Since the 19th century it has been often marked on engraving plates, pictures, photos, postcards and tourist broshures. It's possible to make a whole collection of such images.

On pictures of the European travelers of the 19th century you can see white tombstones near the maqam of sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan. There probably used to be a small Muslim cemetery.

Picture of the maqam sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan (Wilson 1884, II 70)

Picture of 1906

Photo of 1910s

Photo of 1910s

According to W. Khalidi, “The only remaining village landmark is the neglected shrine of Muhammad al-‘Ajami, a low, square, stone structure topped by a formerly whitewashed dome” (1992, 530). In his book, Khalidi published a photo of the maqam of sheikh Muhammad ar-Raslan, confusing it with the disappeared maqam of sheikh Muhammad al-‘Ajami. This erroneous name of the shrine was taken by the following researchers.

Photo of 1987 (from the book by W. Khalidi)

The maqam's interior. (Photo from the book by A. Petersen)

A. Petersen, who studied the maqam in 1991, described it as follows, “This building stands between the lake, and the main road between Tiberias and Qiryat Shimona. The shrine is a small square building with a shallow dome supported by squinches. The shrine is entered by a doorway on the north side (there is also a small window on the same side). There appear to be two tombs inside, one is approximately lm high, whilst the other is marked only by a low kerb of stones. The larger tomb is covered with purple and green cloth” (2001, 210).

View from the north-east

View from the Highway 90

The maqam's interior

Muslim traces are still visible in the maqam. The cenotaph is covered with white and red cloths, green as well, lamps hanging on the wall. Recently the dome was painted green, to tell the truth it was just poured with green paints. An empty can lies in front of the entrance. The painting itself seems to be done in a hurry.

It's worth mentioning that there is no mihrab. One cenotaph stands at the south wall; the second (which A. Petersen described) isn't seen anywhere.

Route: The maqam stands on the side of Highway 90, 500 m to the north of the Migdal junction.

Visited: 21.08.15

Coordinates: 32°49'24.3"N 35°30'58.1"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Guérin, Galilee I 249; Olesnitsky II, 452; Burton 1875, 245; Palmer 1881, 134 (Sheet VI) (“Sheikh er Ruslan”); Wilson 1884, II 70; Stewardson 1888, 140 (“Sheikh er Ruslan”); McCown 1922, 78; Khalidi 1992, 530 (erroneous name “the shrine of Muhammad al-‘Ajami”); Petersen 2001, 210 (erroneous name “the shrine of Muhammad al-‘Ajami”); Schaberg 2004, 49

Addition: Panorama

Tomb of nabi Shuwamin

مقام النبي شويمين

קבר נבי שוואמין

A small Muslim cemetery with a maqam is everything left from Palastinian village Lubya. In 19th century this shrine was called nabi Eshua ibn Amin and it was known to European explorers under such name. Obviously, nabi Eshua stands for the Old Testament Elisha the Prophet (Palmer 1881, 132). On the map of the British Mandate the shrine on this place is called the tomb of nabi Shuwamin (Shwamin). You may suppose that this name is a New-Arabic abbreviation of the same name – nabi Eshua ibn Amin — nabi Shuwamin.

The tomb of the Old Testament prophet highlightened an exceptional importance of village Lubya. Actually biblical Elisha was the son of Shaphat from Abel-meholah (3 Kings 19:16), in Islam Elisha is identified with prophet al-Yasa mentioned in the Koran (6:86; 38-48). Among the Palestinians biblical prophet Elisha might be known as nabi Eshua, and patronym Ibn Amin should be understood as “the son of faith”, “the religious”.

The cemetery of Lubya

The structure (5.0 x 5.0 m) is a domed burial chamber, the walls decorated with arched roof. The entrance in the east wall is partly ruined: the upper part of the wall collapsed. There is no cenotaph in the room. In the south wall there is a high (1.8 m) and quite deep mihrab. Due to the brickwork the tomb can be dated to the middle of the 19th century, some restoration made afterwards. Though obviously the shrine has existed there long before.

It is interesting that this shire is also worshipped by Druzes, who think it is a tomb of the Druze scientist of the 11th century, sheikh Adjara al-Hama. There is a sign “Al Hama Dome” on Highway 77. In book “Druses and holy places” Shimon Avivi says that this structure is the tomb of two Druze religious leaders of the 11th century. The Druzes made a few unsuccessful attempts to capture the shrine.

View from the east

View from the west

View from the north

The tomb's interior

The mihrab

The Arabs succeeded to take control over their shrine, and a few Arabic inscriptions inside the Burial chamber prove that: “Palestine”, “Intifada or Death”, “Soon I will come back to my home”.

Route. The disappeared Palestinian village Lubya was a bit to the west from present Israeli settlement Giv'at Avni. The cemetery of Lubya is located to the north, 300 m from Highway 77. You can reach the tomb of nabi Shuwamin from Golani Interchange. Nearby the junction of Highway 77 there is a petrol station, from which a road goes to the park zone – Lavi forest. After passing this zone you get to the cemetery of Lubya.

Visited: 13.08.18

Coordinates: 32°46'43.5"N 35°25'39.5"E

Location of the object on Google Maps

References: Palmer 1881, 132 (Sheet VI); Stewardson 1888, 13

Thank your for your research. I was investigating about the shrine of Mejdel. However, I think you are wrong the shrine of el-Ajami was north of Mejdel (now disappeared); the one you present is truly the one sheikh Muhammad ar-Razlan. Read Guérin (the link you put) and you will realise that el-Ajami shrine was between the river Hammam and Mejdel. The oldest maps put el-Ajami shrine in the north. Moreover, in this article of 1922 the shrine is definitively not the one one sees today (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3768451?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents)

ReplyDeleteI agree with you. Obviously, this is the shrine of sheikh Muhammad ar-Razlan. And the shrine of sheikh Muhammad el-Ajami was located north of Majdel and does not exist today. If you find images of this shrine, please let me know. Except for an obscure photo https://www.jstor.org/stable/3768451?seq=32#metadata_info_tab_contents

DeletePemakaman muslim I would like to say that this blog really convinced me to do it! Thanks, very good post.

ReplyDeleteThank you.

Delete